React + enzyme + Mocha TDD

React + enzyme + Mocha TDD

Test Driven Development in an insane JS world

With the current state of front-end web development, it’s easy to get lost in a sea of options when it comes to choosing a stack to develop with. The same goes for setting up a test environment; depending on which frameworks you’re using, you might be inclined to use different libraries and test runners to better suit the application workflow and logic.

You can find the source code for this tutorial on Github

So, we’ll go through all the necessary steps to implement a bulletproof boilerplate to get you started with writing tests for React components, using ES2015 syntax (but of course) using the awesome Airbnb’s testing utility, enzyme. While we’re at it, we’ll set up a constant test runner for TDD:

What we’ll cover:

- Set up a simple test setup using React, Mocha/Chai and enzyme

- Cover the basics of wiring things up with Webpack and npm scripts

- Cover the basics of the enzyme library

- Have a working TDD test runner

What is enzyme, first and foremost?

“Enzyme is a JavaScript Testing utility for React that makes it easier to assert, manipulate, and traverse your React Components’ output. Enzyme is unopinionated regarding which test runner or assertion library you use, and should be compatible with all major test runners and assertion libraries out there. The documentation and examples for enzyme use mocha and chai, but you should be able to use your framework of choice.”

You don’t have to use Airbnb’s enzyme library for testing, mind you. It’s completely optional, but I’ve grown to be a big fan of its simplicity. Pair it with Mocha/Chai as our test and assertion libraries, and it’s as painless as testing can get. Also included is a sample Webpack configuration to actually be able to run the development environment, but it will be beyond the scope of this introduction.

Getting Started

Let’s start a project from scratch by downloading and installing the latest version of node.

The structure for this project will be the usual application structure: project in a folder of your choice, our code will live in the src folder and our tests will live under the test folder. Setting up our structure, then:

mkdir src test

And our initial files:

touch src/main.js webpack.config.js index.html

Dependencies and project structure

First off, we know we are going to make use of ES2015 JavaScript syntax. For this to work, we need to install Babel and its dependencies so we can transpile the code, both for the source and our tests. So let’s grab our dependencies, also installing React in the process:

npm i babel-register babel-loader babel-core babel-preset-react babel-preset-es2015 react react-dom --save-dev

That was a lot of dependencies! All we’re doing is grabbing all the presets so we can teach Babel to expect React and JSX syntax, as well as ES2015 code. We’ll wire things up by creating a .babelrc file in the root folder:

touch .babelrc

In this file, copy and paste the following configuration for our project:

{

"presets": ["react", "es2015"]

}

This ensures Babel knows how to handle JSX and the ES2015 syntax we’re writing. Note that we could also have done this in the Webpack configuration file, but I personally prefer to keep this kind of configuration separate from the actual build scripts.

Testing Dependencies

Let’s grab our testing libraries first. We’ll be using Mocha as our test runner, Chai as our expectation library, Sinon for creating stubs and mocks whenever necessary, and Enzyme as a helper library for testing React Components. We’ll go over Enzyme a bit later on, after we set our testing environment up. For now, grab those testing dependencies:

npm i mocha chai sinon jsdom enzyme react-addons-test-utils --save-dev

Setting up the testing framework

Once we have tests and everything wired up, we could manually run the scripts to run Mocha with all the necessary parameters, but we don’t have to. We can make use of npm scripts to achieve this so we don’t have to remember all the command line arguments. Ideally, we want to simply run npm test and have all the magic happen for us.

Open up your package.json file and look for the scripts object. Copy the following:

"scripts": {

"test": "mocha --compilers js:babel-register --require ./test/helpers.js --require ./test/dom.js --recursive",

"tdd": "npm test -- --watch",

"dev": "webpack-dev-server --port 3000 --devtool eval --progress --colors --hot --content-base dist",

"build": "webpack -p"

},

And while we’re at it, let’s also setup a simple Webpack configuration file. Since Webpack isn’t really the scope of this tutorial, grab the configuration from the repo for our webpack.config.js file.

Before moving on, let’s have a closer look at our test npm test task:

"test": "mocha --compilers js:babel-register --require ./test/helpers.js --require ./test/dom.js --recursive"

You may notice that we’re requiring two files we still haven’t created. helpers.js will be a helper file with some globals we’ll be using for tests (so we don’t have to import them all the time), and dom.js will create a fake DOM environment for them. The --recursive flag will make Mocha look for all files and directories under the test folder.

Helper files

So let’s create the test/helpers.js file, and include the following:

import { expect } from 'chai';

import { sinon, spy } from 'sinon';

import { mount, render, shallow } from 'enzyme';

global.expect = expect;

global.sinon = sinon;

global.spy = spy;

global.mount = mount;

global.render = render;

global.shallow = shallow;

And test/dom.js will have our mocked DOM:

/* dom.js */

var jsdom = require('jsdom').jsdom;

var exposedProperties = ['window', 'navigator', 'document'];

global.document = jsdom('');

global.window = document.defaultView;

Object.keys(document.defaultView).forEach((property) => {

if (typeof global[property] === 'undefined') {

exposedProperties.push(property);

global[property] = document.defaultView[property];

}

});

global.navigator = {

userAgent: 'node.js'

};

Writing our first test

In proper TDD fashion, let’s write the first test for our initial, yet unwritten React component! We’ll write a simple component which will be a comment item, containing an <li> tag with custom text.

Let’s create the test file: touch ./test/Comment.spec.js

The tests are written in the traditional “describe, it should, expect” fashion. If we were to write the simplest of a passing test, we could do the following:

describe('a passing test', () => {

it('should pass', () => {

expect(true).to.be.true;

});

});

And indeed, true is true, so that passes. So let’s focus on our Comment.spec.js file. We want our Comment component to be of type <li> and to receive a custom comment, also having a class name of comment-item.

import React from 'react';

import Comment from '../src/components/Comment';

describe('Comment item', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<Comment />);

it('should be a list item', () => {

expect(wrapper.type()).to.eql('li');

});

});

Notice that we don’t declare expect or shallow in this file. That’s because all these references are being imported by our helpers file. Notice that for this, we’re using shallow() from enzyme’s API. Checking for types and classes, we don’t actually need to mount or render the components, so shallow is more than good enough here.

If we run npm test now, our test will fail because we still haven’t written our component. So let’s open up src/components/Comment.js and create it.

enzyme: shallow, mount, render… what?

Before we continue, it’s worth having a look at enzyme’s API. It gives us three separate ways of rendering a component, so it’s not always clear which one we need for our tests.

Starting with shallow:

Shallow rendering is useful to constrain yourself to testing a component as a unit, and to ensure that your tests aren’t indirectly asserting on behavior of child components.

mount, also known as full-rendering, gives you a bit more:

Full DOM rendering is ideal for use cases where you have components that may interact with DOM APIs, or may require the full lifecycle in order to fully test the component (i.e., componentDidMount etc.)

And finally render, which refers to static rendering:

Enzyme’s render function is used to render react components to static HTML and analyze the resulting HTML structure.

Creating a Component

import React, { Component } from 'react';

class Comment extends Component {

render() {

return (

<li className='comment-item'>

<span>I am a comment</span>

</li>

)

}

}

export default Comment;

Run npm test again and our test should pass, since our component is of type <li>. Now, onto the custom text and class names.

Checking for props

Our comment item is hardcoding a comment text value, but it should expect to receive from props a comment text. Using enzyme, we can update our test to tell it to expect this behaviour and check if it matches. We can use the contains() function to check if any string is included in the rendered markup.

Let’s write another assertion for our test file:

it('renders the custom comment text', () => {

wrapper.setProps({ comment: 'sympathetic ink' });

expect(wrapper.contains('sympathetic ink')).to.equal(true);

});

We can customise the props of our instance component by using enzyme’s setProps() method. Since the Comment component is hardcoding the text, this will fail!!

So let’s fix that by making our Component behave like the test expects, changing the span tag to:

<span>{this.props.comment}</span>

And now it works!

Checking for class names

There are several ways to check for class names using enzyme. With shallow rendering, you can make use of the hasClass method or the find() (you can check the API here). Here’s an example for our Comment:

it('has a class name of "comment-item"', () => {

expect(wrapper.find('.comment-item')).to.have.length(1);

});

The assertion speaks for itself: find an element with a class of .comment-item and expect to find just 1.

Tip: We could also use hasClass() to test if a given component also has a certain class. A very useful example for this is checking for is-enabled or is-active classes once an action happens in your component.

Testing React lifecycle methods

Checking and testing for simple assertions like class names and the existence of tags is very simple, but very often not enough. For example, what if we wanted to check if our React’s lifecycle methods were called?

Let’s create another component, one that will display our individual comments. Let’s call it CommentsList.js in our components folder.

Since the purpose here is to show the test methods we can use to test the components, I’m going to skip the TDD approach and write the component first, so here’s what it looks like:

CommentsList.js

import React, { Component, PropTypes } from 'react';

import Comment from './Comment';

class CommentList extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = { comments: [] };

}

componentDidMount() {

this.setState({

comments: ['Comment number one', 'Comment number two']

});

}

renderComments(comments) {

return comments.map((comment, idx) => <Comment key={idx} comment={comment} />);

}

render() {

const commentsNode = this.renderComments(this.state.comments);

return (

<div className="comments-list">

{commentsNode}

<button onClick={this.props.onButtonClick}>A button</button>

</div>

)

}

}

export default CommentList;

It’s a component that starts with an empty array state which, when it mounts, receives a list of comments that then becomes the new state. With them, it renders several instances of our previously defined Comment component.

Testing React lifecycles

So let’s create our test file for this new Component, CommentsList.spec.js. To test if componentDidMount really triggered, we can use sinon to spy on this lifecycle method. However, since we need to mount the component in order for it to render, we need to use enzyime’s mount() instead of the shallower, shallow().

We can write the following assertion:

it('calls componentDidMount', () => {

spy(CommentList.prototype, 'componentDidMount');

const wrapper = mount(<CommentList />);

expect(CommentList.prototype.componentDidMount.calledOnce).to.equal(true);

});

(Remember that we also exported the sinon and spy global variables in our helper file, so we don’t have to require/import them.)

Using sinon and its spies is also what you’ll want to use to check if certain methods and actions run once something in your component is clicked, for example.

Testing Events, such as ‘click’

If you look at our CommentsList.js file in the repo, notice that there’s a button.

Now here is a challenge

As a User I want to be able to click on the button so that my comments are reversed.

In our case lets write an intergration test. Here’s an example of a test for this:

it('reverses the comments on the button click', () => {

const wrapper = mount(<CommentList />);

wrapper.setState({ comments: ['hello'] });

wrapper.find('button').simulate('click');

expet(wrapper.state().comments[0].to.equal('olleh'))

});

Here’s a quick brainstorm :

- mount the component;

- set its state manually to a comment of ‘hello’;

- find the button and simulate a click on it;

- expect the comment (first item in the array) to be its reversed text

- Hint you will have to implement the method that does the reverse in order to make the test past

TDD

There’s no excuse not to practice TDD. This means allowing your test to dictate your design and implementation, have a failing test first and make it pass.

Runner

In package.json we have a watcher keeping the test suite always running. Go ahead and run npm run test:watch.

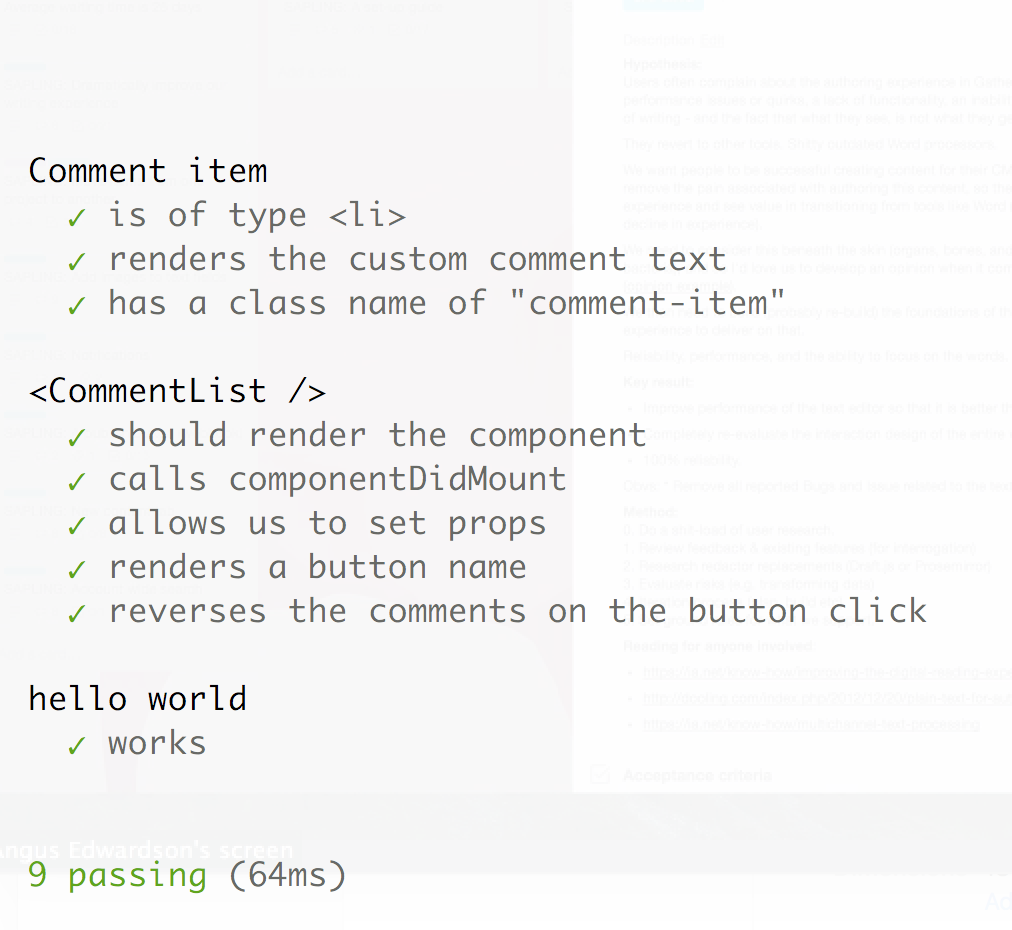

And voila you have a runner ![]()